Chasing Counter Seasonality

How Peru built scaffolding to become the leading exporter of blueberries

In the mid-1800s, hundreds of international ships lined up at Peru’s Chincha islands to get their cargo of “guano”, a very important agricultural input. Guano is bird-droppings from millions of birds and is a very effective nitrogen fertilizer. The guano trade ended with depletion of guano, regional wars, and the scaling of the Haber-Bosch process in the early 20th century.

About 150 years later (today), less than 200 miles north of the Chincha islands, ships line up to get into the brand-new deep-sea, highly automated Chancay port, which opened in November 2024.

The stevedores of Baltimore from “The Wire” would have been totally against this port.

The ships are there to carry minerals, industrial goods, and, most importantly, agricultural outputs such as blueberries, avocados, grapes, and mangos. Most of the cargo is headed to China and other parts of Asia.

Not only is the Chancay port new, but some of the products in those containers, such as blueberries, are relatively new exports for Peru. In fact, Peru didn’t produce and export many blueberries till about 10-15 years ago.

The growth of blueberry exports is a good story of what can happen when public and private enterprises come together, build critical infrastructure, enable the right policies, and provide support for the right technology.

Counter seasonality

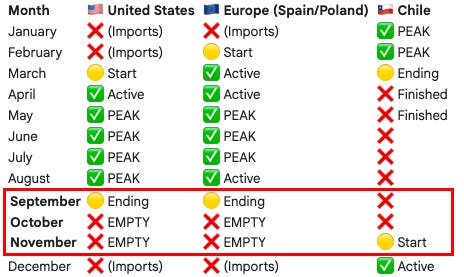

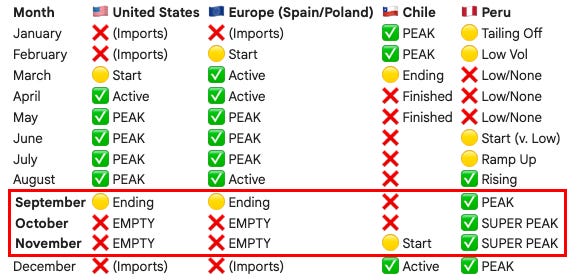

About 15 years ago, if you went to your local grocery store to buy fresh blueberries in October or November, you would have a very tough time finding them. This is due to the fact that the main blueberry growing regions of the world, the United States (mainly California), Europe (Poland and Portugal), and Chile, did not harvest many blueberries during the September through November time period.

So, if you could grow blueberries such that they could be harvested during September through November, and you could have the logistics infrastructure to get the blueberries in different parts of the world in a timely manner, you could command high prices during that time period.

You can be the only game in town for a quarter of the year!

This is exactly what Peru has achieved. But to begin with, blueberries are not native to Peru.

The conventional wisdom was that blueberries could not grow in Peru because the plant typically requires “chill hours” (prolonged periods of cold weather) to flower, which the Peruvian coast lacks.

But industry pioneers began experimentation in the middle of the ‘oughts. They brought different varieties to Peru to test if any could adapt to the coastal desert climate.

The industry discovered that certain varieties (most notably Biloxi) could thrive in the mild climate of the Peruvian coast without requiring deep cold. They treated the crop almost like a tropical evergreen rather than a temperate bush.

By managing water and nutrition precisely, growers realized they could “force” the plants to flower and fruit at specific times, allowing them to control the harvest window.

Because the weather is stable, Peruvian growers can prune their plants to ensure they produce fruit exactly when prices are highest globally (September–November), the window when the US and European harvests are finishing, and the Chilean harvest hasn’t fully started yet.

This gives Peru’s blueberry business a unique advantage, assuming they have the supporting infrastructure of reliable demand, logistics, and irrigation infrastructure, the ability to experiment to be able to realize and capture the most customer value, and a policy framework that allows the business to thrive and grow.

As we will see soon, all of these factors came together to make Peru a blueberry powerhouse in less than 20 years.

The Usain Bolt of Blueberries

One of the challenges in establishing a new blueberry crop is that a blueberry bush may take 3-4 years to reach full production, especially in traditional regions such as the United States and Canada.

But in Peru, due to the climate and genetics, blueberry plants can begin producing commercially in their first year.

Peru blueberry bushes grow fast and reach harvest maturity in just over half a year. As in the US, in Chile and Argentina, they grow in three years. The huge difference in growing time accelerates both productivity and learning. Peruvian firms can conduct 3-4 times as many experiments with different varieties and crop management techniques.

In Peru, because there is no winter dormancy, a plant enters commercial production in its first year. This allows investors to get their money back much faster. The short time-to-cash flow with blueberries (assuming you have demand and a logistics network) allows for lower investment and less deep pockets to experiment with blueberries in Peru, compared to other parts of the world.

This accelerated learning process cannot be underestimated. The Peruvian coast is an arid desert with stable temperatures and acts as a natural open-air greenhouse. This allows Peru to harvest blueberries year-round, though it typically targets specific windows to command the best prices.

Stable temperatures in Peru provide greater control over “programming” and demand locking-in, thanks to their reliable supply. For example, if Peruvian growers want fruit in October to fetch high prices, they prune blueberry plants 5-6 months before harvest. This reliability (not available in California because weather dictates harvest timing) allows Peruvian growers to sign large, guaranteed contracts with major grocery retailers.

Blueberries are labor-intensive (hand-picked). Peru has access to a large agricultural workforce in the north at much lower prices than in California (La Libertad/Lambayeque). In California, finding enough workers during harvest is a chronic crisis, often forcing farmers to leave fruit on the bush or invest in expensive mechanical harvesters.

Genetics to the rescue

Because the Peruvian industry is young (circa 2012), most of their fields are planted with modern, high-yield varieties. California has many older fields with legacy varieties that are less efficient and have softer fruit.

In terms of fruit profile, Peruvian growers prioritize blueberries that are vigorous, firm, extra-large, sweet, less acidic, and crunchy. These qualities make the berries ideal for international markets. Maintaining the in-field characteristics and quality of berries from production to consumption requires specialized genetics and logistics.

Companies like Camposol, Inka’s Berries, and Agrovision (now called Fruitist) did multiple trials to determine the best Chilean blueberry varieties suited for Peru’s climatic conditions. With its counter-seasonality advantage and fast-growing berries, Peru has captured a large share of the international export market. Now, Peruvian growers are working to increase value by developing more innovative products through genetic research and identifying new varieties.

For example, newer varieties like Ventura are larger and sweeter than Biloxi, yield fruit earlier, and allow growers to hit the high-price window in August and September. Super varieties like Sekoya Pop (and Sekoya Beauty) prioritize a “crunch” texture, a long shelf life (45+ days, which is vital for shipping to Asia), and a jumbo size.

Infrastructure and Policy Support

Despite the chronic political instability in Peru (8 presidents in the last decade), the Peruvian state has provided the necessary infrastructure and policy support for the blueberry business to flourish and for Peru to become one of the world’s largest exporters of blueberries.

One of the architects of the policy framework is Pierro Ghezzi, the former minister of production for Peru. You should see his January 2026 interview with Vox Dev. He mentioned four key policy pillars that underpinned the agro-export boom along with logistics.

Pierro Ghezzi highlighted the role of “Mesa Ejecutivas” (Executive Roundtables or ERs) in the Global Policy publication and the Inter-American Development Bank article, “Executive tables in Peru: A technology for productive development.”

Latin American countries face the challenge of sustainably increasing their productivity. Changes in production methods toward modern methods across various sectors, including natural resources, and in private-sector regulations and standards, offer opportunities.

These increased coordination needs cannot be met with standard public policies or traditional industrial policies. A modern industrial policy is required, one that must be a process of strategic public-private collaboration. It must include learning, experimentation, coordination, monitoring, evaluation, and correction.

The main objective of the ERs (Executive Roundtables) is to identify the constraints that limit the productivity of a sector or a factor and to implement solutions to eliminate them. Their focus is on execution, not on generic dialogues about competitiveness. But experience shows that execution provides a clear direction.

The Executive Roundtables (Mesa Ejecutivas) provided a key unifying and continuous structure to push through many policy changes and provided continuity despite a volatite political situation.

Free-trade agreements

Peru established a free-trade agreement with the United States in 2009. Peru also has free trade agreements with the EU, UK, ANZ, Mercosur countries, Japan, Mexico, China, and many other countries. In return, Peru permits certain types of foreign direct investment.

The trade policy has ensured that if Peru can provide high-quality products at competitive prices, there will be a market for them in different parts of the world.

Water in the desert

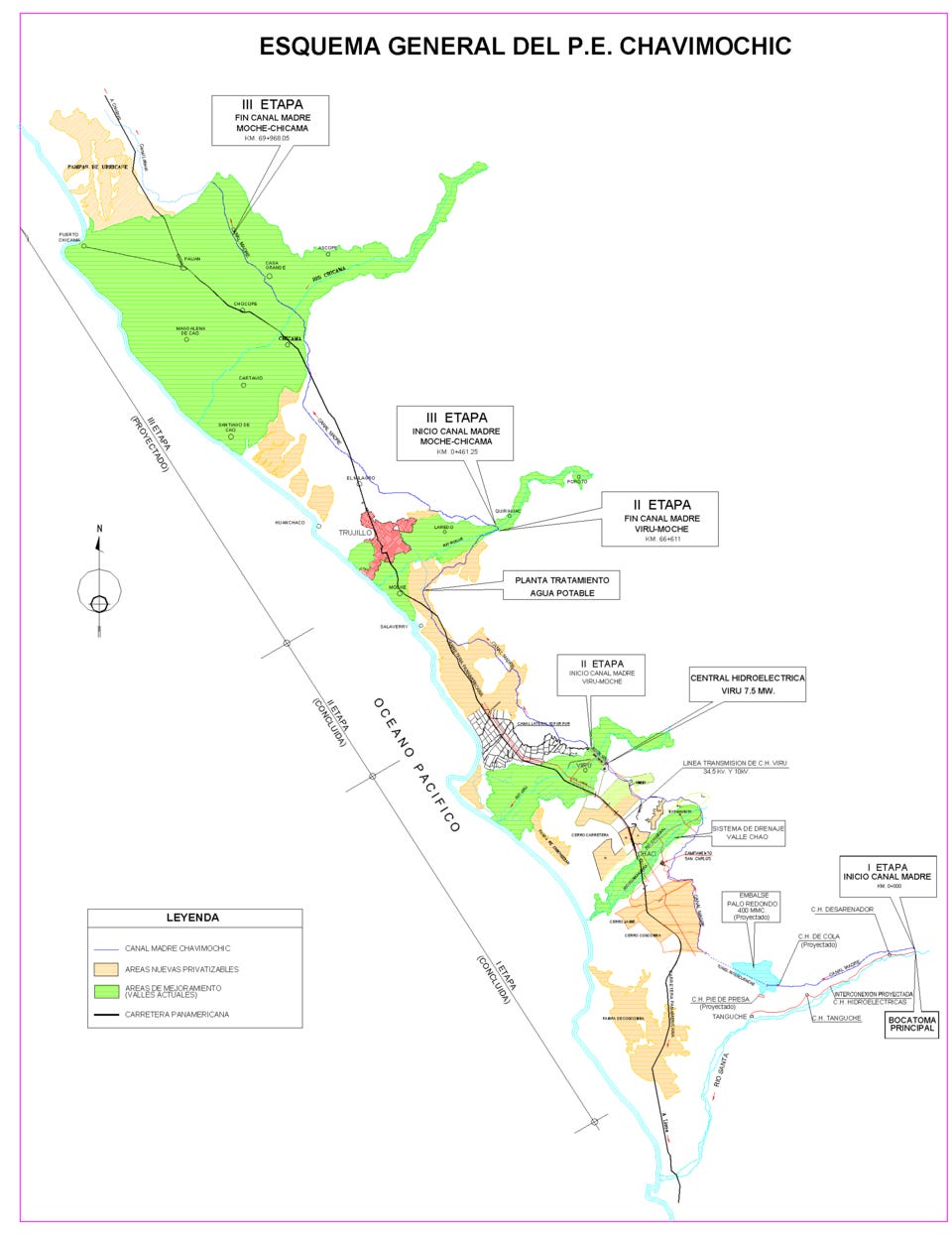

The coastal desert of Peru receives almost zero rainfall (less than 10mm per year in some places). The coastal desert is not suitable for agriculture without human intervention to bring water there for irrigation. On the east side of the coast, the mighty Andes are snow-capped, and rivers flow out of them, but no major river comes to the desert. The idea of drawing water from the Santa River and creating north-south canals was conceived in 1912. Construction began in the 1960s, and Phase 3 began in 2012.

It takes water from the Santa River (which flows down from the Andes) and diverts it through a massive 150km+ network of open-air canals and tunnels that run north along the desert coast.

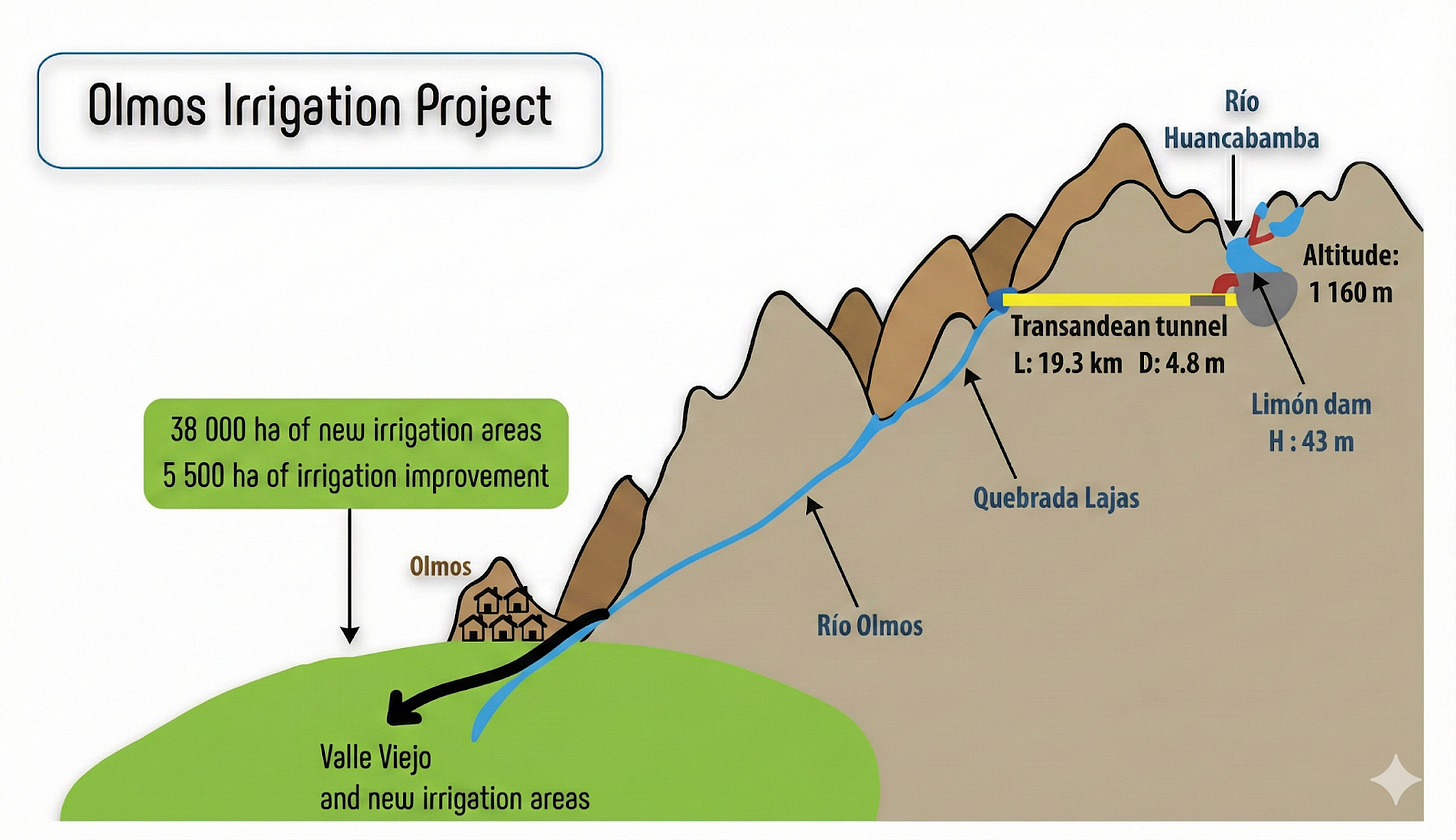

In another ambitious project (Olmos Irrigation Project), which was initially conceptualized in 1924, but real work started on it in 2006, brings the waters of the River Huancabamba through a 20 km long Trans-Andean tunnel through the Andes. Once the first phase of the tunnel project was operational, the scheme supplied more than 2 billion cubic meters (500 billion gallons) of water annually to irrigate 130,000 acres of farmland.

The project is an engineering marvel. It takes water from the Huancabamba River (which naturally flows east toward the Amazon/Atlantic), captures it with the Limón Dam, and forces it through the tunnel to the dry Pacific side. (as shown in the schematic below).

These two massive public irrigation projects created large, efficient, industrial-scale plots that are perfect for mechanical harvesting.

Phytosanitary

When it comes to fresh produce, you need to prove to your buyer (especially in the case of exports) that your product is not going to bring pests to their country. There is a reason why, as individual passengers, we are not allowed to carry fruits and vegetables across borders. One time, a friend of mine was fined $600 for bringing a single mango into the United States!!

Peru’s government agency, SENASA (National Agriculture Health Service), played a key role in certifying and enforcing standards to assure buyers that Peruvian fruit is free of pests. Initially, Peruvian growers used methyl bromide asa chemical fumigant for post-harvest treatment. Fumigation affects fruit quality, including softness and reduced shelf life.

When Peru finally struck a deal with China, it followed the temperature-controlled cold chain method of storing and transporting blueberries at a temperature below a certain threshold for 3 weeks. This kills pests without fumigation but requires a highly efficient and reliable cold chain.

Lately, Peru has been using a systems approach to certify fields instead of the final product. If the fields are shown to be pest-free, the fruit can be exported as natural, without any treatment. This allows them to compete for higher-value products, such as the organic, premium, crunchy berries category.

Peru’s special efforts on phytosanitary have given it the freedom to operate in various regulatory environments and have given the authorities and consumers confidence in Peruvian blueberries (and other products)

Sector-specific agrarian law

The Peruvian government enacted the Agrarian Promotion Law in 200, which reduced the income tax rate for agricultural enterprises to 15%, accelerated depreciation for agricultural investors, and made the sector attractive to investors. This helped fuel additional investment, provided more time for experimentation, and catalyzed the development of Peru’s blueberry sector.

The law was modified in 2021, raising the income tax to 30%. These modifications could lead to a decline in future investment.

Logistics infrastructure

As I said at the beginning of the piece, Peru opened a brand-new deep-sea port in Chancay by utilizing financing and support from China’s Belt and Road Initiative. The port has reduced the shipping time from Peru to China from 35-40 days to just 3 weeks. This significant reduction allows Peru to ship fresh berries (with limited shelf life) to China by water rather than by air freight.

Peru’s ability to move perishable products quickly gives it a competitive advantage. The Pan-American Highway, with its cold-chain supporting infrastructure and farm-level vertical integration through large growers, can move fruit from farms to ports quickly and efficiently without sacrificing quality.

Peru’s continuous harvesting capability and flexibility give it a competitive edge over countries reliant on seasonal farming. Here, the Biloxi variety stood out. Optimal for production from late August to early December, Biloxi blueberries had a key market advantage: they avoided direct competition with northern hemisphere supplies (harvested May-August).

A perfect storm for rapid growth

One way to think about the growth in blueberry exports from Peru is to think that it happened in less than 20 years. Another way to think about it is that it took almost 100 years for some of the irrigation projects to come to fruition.

One thing is clear that for the Peru’s blueberry industry to take off, it needed many factors to come together at the same time to take advantage of the counter-seasonality possible for blueberries, whether it was to find the right markets, public-private partnerships, logistics capabilities, policies for product safety and reliability, favorable tax and investment environment, and an irrigation infrastructure built over decades.

Other growing regions can take lessons from Peru’s blueberry adventure. A large-scale positive change requires multiple factors, such as technology, policy, trade, and infrastructure, to come together.

If you want to bring about large-scale change, you need to identify your edge (like Peru did with counter-seasonality for blueberries) and work with the ecosystem to catalyze it and drive positive change. These changes don’t happen overnight and can take 15-20 years (or a few decades).

Interesting article. Was glad to see Fruitist blueberries mentioned as they are deliciously juicy and found to enjoy at the local Publix. Fascinating to know the source of our food as opposed to Ayn Rand’s dismay that people think food comes from their grocer and not grown and transported with great thought, time, and effort.

Thank you for sharing.

As someone who g rew up (and still does) pick wild blueberries for personal use, I'd be interested to know if any of the new varieties of cultivated blueberries are thought to have equaled the intense flavor of wild ones. It's not hard to find cultivated ones that are sweet enough (though plenty are quite sour) , but the deep flavor seems to be missing.