Flooding in the desert

Water challenges in the Yuma desert

Yuma, Arizona, gets about 3 inches of rainfall every year. This classifies it as a hot-desert climate. But during the lettuce growing season, it is common to see fields using flood (gravity) irrigation.

“Flooding” in the Yuma desert is quite common.

The waters of the Colorado River, the irrigation infrastructure, Yuma’s senior rights for the water of the Colorado River, abundant sunshine 330 days a year, good soil, and advances in technology created a perfect storm for Yuma to become the winter salad bowl. The Colorado River’s water availability may become challenging in the future, potentially triggering changes in Yuma’s agricultural landscape. This week’s newsletter goes back in time to the history of Colorado's waters, how things are changing, and ultimately what it means for AgTech innovation in the future. Last week’s newsletter focused on the automation of lettuce harvesting in Yuma, and it is a good companion read with this week’s edition.

I recently spent 2.5 days in Yuma. I landed in Phoenix early in the morning, and we drove to Yuma, about a 3-hour drive.

You leave the urban landscape of Phoenix behind you and keep going down from an elevation of 1100 feet to 150 feet as you go to Yuma Valley.

You encounter the massive Saguaro cactus, which looks like Poseidon’s giant tridents towering over the landscape. It is ironic, given Poseidon’s trident symbolizes power over oceans and waves, but the landscape is arid and moonlike.

Driving over the Gila Mountains and Telegraph Pass (about 20 miles east of Yuma), as you drop into Yuma Valley, the stark desert is replaced by a massive, lush green grid of industrial agriculture (lettuce, leafy greens, etc.).

The waters of the Colorado River and the amazing irrigation infrastructure built over a few decades are one of the main reasons to turn this “desert” into the winter salad bowl of the United States.

According to the Arizona Water Factsheet, Yuma County, (November 2025)

Nearly all surface water in Yuma County comes from the Colorado River, which is the only source of water for communities located adjacent to the river.

Colorado water is used by 7 US states and Mexico. How the water of the Colorado River is divided up was decided by the Colorado Compact in the 1920s.

It is important to understand the history and numbers behind the Colorado Compact, the assumptions it makes, how it has affected Yuma agriculture, how it will impact the future of Yuma agriculture, and what it means for AgTech innovation.

The Colorado Compact

In the early 20th century, the seven southwestern and western states of Arizona, California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and Wyoming created an agreement to manage the river’s water by dividing into the Upper Basin (CO, NM, UT, WY) and Lower Basin (AZ, CA, NV). The agreement was established in 1922 and is called the Colorado River Compact.

This agreement and subsequent negotiations dictate how water is shared among these states and Mexico (because the Colorado River flows into Mexico and into the Gulf of California).

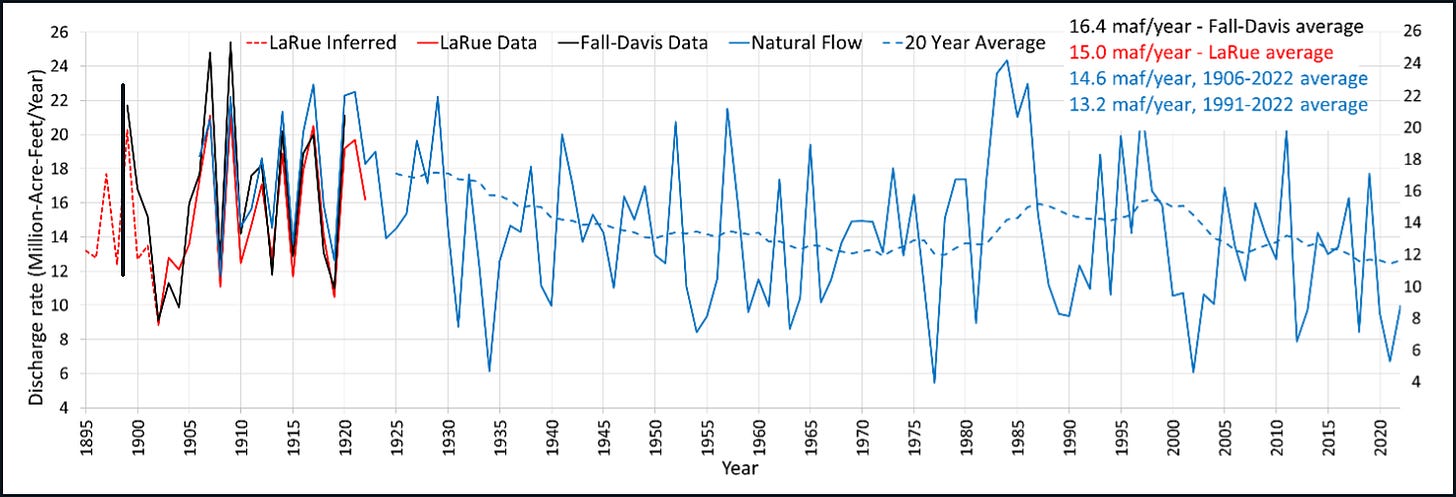

One of the biggest issues in setting up the Colorado Compact and in how water is shared between states was an overestimation of how much water the Colorado River carries over the long term.

The agreement used data on water flow from 15-20 years prior to the contract to determine how much water would flow to the Upper and Lower Basins.

The fly in the ointment is that the 15 years preceding the agreement were among the wettest on record, so it overallocated 7.5 million acre-feet to the Upper Basin and 7.5 million acre-feet to the Lower Basin states, for a total allocation of 15 million acre-feet.

The data for the 15 years preceding the 15-year period used for the agreement showed a total water flow of only 13.5 million acre-feet, and the long-term average for the Colorado River is closer to 13.5 million acre-feet and is declining.

According to the EOS report,

“The allocation of 7.5 million acre-feet per year of consumptive use for each basin was grounded neither in the best available hydrologic calculations nor in climate variability projections. Rather, it was a compromise Hoover proposed between two endmember figures [Kuhn and Fleck, 2019]. One end was 8.2 million acre-feet per year, half the assumed annual average discharge at Lee Ferry of 16.4 million acre-feet per year, which itself was derived from a report by the U.S. Reclamation Service (now the Bureau of Reclamation) [Fall and Davis, 1922]. The other end was 6.5 million acre-feet per year, a figure proposed and advocated by the Upper Basin commissioners that reflected a roughly 50-50 split of the river discharge at Yuma [Kuhn and Fleck, 2019].

In the decades following the 1922 compact, a plethora of acts, orders, and agreements were written and signed to fine-tune the compact’s provisions, to authorize construction of dams for water storage and power generation, to build water transfer infrastructures, and to resolve interstate and intrastate disputes. Particularly significant was the 1944 treaty between the United States and Mexico—still in effect today—that guaranteed 1.5 million acre-feet of Colorado River water annually for Mexico, bringing the total allocation to 16.5 million acre-feet per year.”

Hydrologist Eugene Clyde La Rue, who had studied the Colorado River for quite some time, argued that decision-makers should use longer- term averages in estimating river discharge, which were not used.

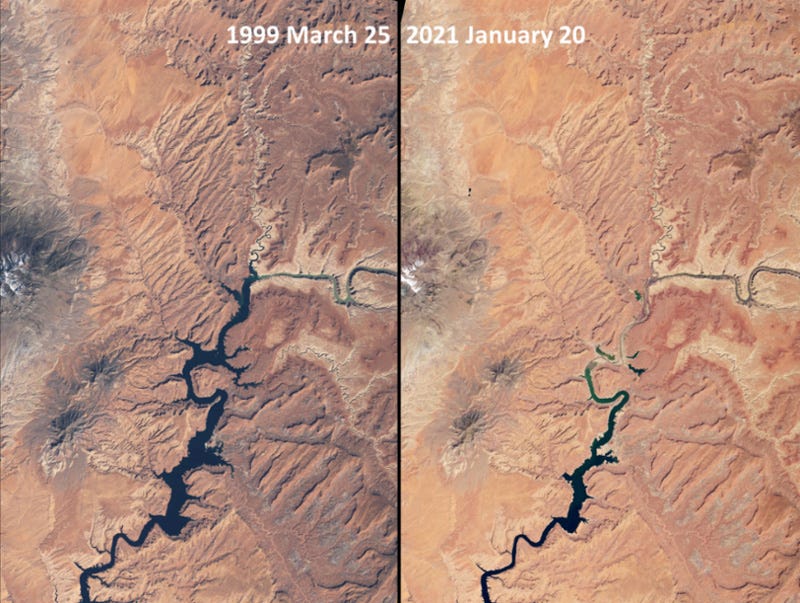

The amount of water flowing down the Colorado River has decreased over the years (or fluctuated significantly), creating interesting issues for water allocation under a priority-based access system. There is also an issue with the allocation of water to tribal homelands.

According to Wikipedia,

Since 2000, dwindling Colorado River flows and consumption rates in excess of natural replenishment have provoked a need to plan for shortages. Because of its lower priority, shortages should fall primarily upon the users of the Central Arizona Project, the consequences for some Arizona farmers and urban sectors could be dire. If the federal government acts unilaterally to restrict other water uses, it risks litigation. For these and other reasons, river users are exploring voluntary measures to address shortages.

The Colorado Compact does not have an end date, but some of the interim agreements negotiated in 2007 are set to expire in 2026 (this year!). The Bureau of Reclamation is leading a process to develop long-term management plans, with a draft Environmental Impact Statement released in January 2026, aiming for new guidelines by October 2026 before the next water year begins.

It is safe to say that access to and allocation of water for agricultural irrigation (which accounts for 97% of Yuma's freshwater use) could be a challenge in the future.

Gravity is free

Based on the reading so far, one might not be wrong to think that, given the water challenges in the present and the future, Yuma might be moving to the most efficient irrigation system in the world: drip irrigation.

But changing a particular practice can have a cascading effect.

The whole lettuce growing business is a finely choreographed dance. A five-degree difference in temperature is used to start planting in one part of Yuma Valley, and as temperatures go down further, planting spreads to other parts of the valley.

The irrigation method used during the early part of crop growth depends on whether the crop is direct-seeded (seeds sown directly into the ground) or transplanted from another location. These practices have been refined over many years and are closely intertwined.

So if you come in with a technology solution that changes one practice, you have to really understand the impact of that change for this finely tuned system, you will end up with solutions that do not work or cause adoption challenges.

Coming back to irrigation, leafy green production (lettuce, spinach, kale) in Yuma uses a specific hybrid irrigation strategy that surprises many people because it relies heavily on “old school” flood irrigation methods that have been optimized with high-tech precision.

They typically do not use drip irrigation throughout the crop's lifecycle. Instead, they switch methods halfway through the season.

Most lettuce fields in Yuma follow a strict two-phase irrigation schedule, especially for direct-seeded crops. During the germination phase, aluminum pipes with sprinkler heads are laid out by hand across the field immediately after planting seeds. The sprinklers cool the soil and protect the seed. It ensures that every inch of the seedbed gets wet, to guarantee a uniform “stand” of lettuce

Once the plants are a few inches tall (after “thinning”), the sprinkler pipes are removed. Water is then sent down small trenches (furrows) between the rows of crops. The water comes from a network of open canals that start at the Colorado River, and water allocation is controlled by the local water districts. Growers siphon out water from the canal through movable pipes and send it down furrows.

The Colorado River is salty. Sprinklers can leave salt crusts on the leaves as water evaporates. Furrow irrigation pushes those salts down below the root zone to prevent salt burn.

Ideally, the water seeps sideways into the roots without ever touching the leaves. Yuma has heavy alluvial soil that holds water well, allowing it to flow down a furrow without sinking immediately. This is important for food safety, as the water stays on the ground rather than on the leaves. It minimizes the risk of pathogens touching the edible part of the plant.

Even if Yuma could be looking at water issues, drip irrigation might not always be the answer, due to another “green” commodity - dollars!

Lettuce is a fast crop (60–90 days). Installing and removing drip tape for every rotation is incredibly expensive and labor-intensive. Drip irrigation can push salts to the edge of the wet zone (right where the plant roots are), whereas furrow irrigation flushes the salt deep down.

A big expense would be the energy required to make drip irrigation work. The energy requirements can make drip irrigation quite expensive, whereas furrow irrigation (flood irrigation) does not require energy.

As one grower said,

Gravity is free.

Even though furrow irrigation looks primitive, Yuma farmers have made it about 80–90% efficient using Laser Leveling. Before planting, GPS-equipped tractors and laser systems grade the fields to be perfectly flat or have a microscopic slope.

This level of precision ensures water flows at “Goldilocks” speed. The flow is fast enough to reach the end of the row, but slow enough to soak in evenly without pooling or running off.

So even though the cost of water is lower with a drip system, the setup costs (PVC mainlines, plastic drip tape, etc.), energy costs, and maintenance costs increase the total cost of ownership and operations for a crop like leafy greens.

Having said that, due to water challenges, growers have been shifting the crops they grow and adopting efficient methods such as laser leveling, newer genetics, and fertilizers to become more water-efficient. Modern lettuce varieties grow faster and are denser, requiring fewer irrigation runs due to a shorter season.

For example, the water fact sheet for Yuma County from the University of Arizona says,

Water used for irrigation in Yuma County has decreased 15% since 1990 based on a reduction in irrigable acres, expanded use of multi-crop production systems that require less water, and significant improvements in crop and irrigation management and infrastructure. The number of acres planted to vegetables has increased nearly 6x over the past 40 years, while acreage committed to full-season crops (citrus, cotton, sorghum, and alfalfa) has declined 43%.

Given the context of the water situation, climate change, and labor challenges (which we covered last week), one might be tempted to focus heavily on reduced water use, whereas the challenge is how to allocate water (which itself might be changing) most efficiently.

Given this context, what types of solutions should the AgTech ecosystem consider for Yuma?

What does it mean for AgTech?

AgTech innovation in Yuma must pivot from a pure optimization mindset to one of resilience, embracing diverse, evolving farming practices that adapt to new technologies and a harsher environmental reality.

Genetics

As I said earlier, climate change and heat might shrink the growing window for Yuma. If geneticists can develop heat-resistant crops, they can help protect or extend the shoulder season. Expansion of the shoulder season helps protect or restore profitability lost to extreme weather events or climate change.

Any technology that can reduce field temperatures during the shoulder season could also protect or expand the growing window in Yuma, potentially increasing profitability.

Also, there is a salinity time bomb over a reasonably long horizon, as the Colorado River is getting saltier. It might require genetically modified crops designed to tolerate higher salinity water.

Photovoltaics

As and when water becomes expensive, the sun might become one of the cheapest assets of Yuma. The integration of solar panels over crop canals and fields can reduce evaporation, and transpiring plants can cool the solar panels. The development of lightweight, translucent solar arrays that let through the exact light spectrum plants need for photosynthesis while blocking the heat-generating infrared rays.

Tracking salt and heat

Current soil moisture sensors can measure soil moisture, but it is difficult to map and monitor salinity in a field. Cheap sensors that can track EC and canopy temperature can help growers make better decisions.

Water accounting

As the government starts paying farmers not to farm, there is a massive need for technology that verifies that water was actually conserved. AgTech companies that can become the QuickBooks of Water could be quite valuable.

Automation to address labor issues

As I said last week, there are challenges with labor access, and labor costs are rising. The labor force is also aging and shrinking. Crop robotics for weeding, thinning, and, most importantly, harvesting will be key areas for the AgTech ecosystem. We might also have the need to breed “robotics-ready crops”.

For example, lettuce varieties that grow on longer stalks or have uniform shapes designed to be grabbed by a machine, even if they look slightly different than what consumers want.

Connectivity infrastructure

It will be difficult to implement automated, autonomous systems on farms without connectivity, which is a challenge in Yuma. Yuma is tackling that problem head-on by building a “middle mile” fiber-optic network to provide high-speed internet access at the farm and field levels. With the ease of creating “edge computing” devices, connectivity becomes even more important to help control and manage remote equipment.

Conclusion

The agricultural landscape of Yuma is a complicated web of historical, social, political, cultural, economic, environmental, and technological issues. The Colorado River, the amazing irrigation infrastructure, and the resilience and ingenuity of growers have created the “winter salad bowl.”

The complexity is similar to that of other agricultural regions, but it has its own set of considerations. As the underlying factors change, the agricultural business built on them will have to evolve over the coming years.

Technology will play a key role in the process.

Rhishi, this is one of the most grounded field notes I’ve read on Yuma. The “flood irrigation in a desert” paradox is exactly the kind of thing that looks irrational until you see the system.

Here are a few reflections through my systems thinking lens:

1) Yuma isn’t “behind.” It’s locally optimized against real constraints. What you captured (hybrid irrigation, salinity management, food safety, short-cycle economics, gravity economics) is a reminder: practice-level “upgrades” fail when they ignore choreography. The system is doing what it was designed to do.

2) The real fragility isn’t irrigation efficiency. It’s governance volatility. Post-2026 rule shifts are a system rules change. When the rules governing the critical input (water) become uncertain, even a highly optimized region becomes brittle. That’s the transition we’re entering.

3) “Resilience” isn’t a mindset. It’s engineered capacity. In my Regenerative Systems Theory(RST) lens, resilience emerges when the five gears reinforce each other:

- Nature: water scarcity + salinity + heat are the binding constraints (not optional variables).

- Design: Yuma’s hybrid irrigation + laser leveling is resilience architecture in disguise (buffers + modularity).

- Community: irrigation districts, labor networks, harvest timing, food safety regimes coordination cost is the hidden adoption killer.

- Self: growers are managing high-cadence decisions under increasing volatility; survival mode is rational unless volatility is reduced.

- Capital: if resilience isn’t paid for (contracts, insurance, underwriting), it won’t scale.

4) The AgTech pivot is not “from optimization to resilience”. It’s from optimizing practices to stabilizing systems. Your solution directions are spot on, and I’d frame them as “resilience infrastructure” categories:

- Decision-grade sensing (EC + canopy temp) upgrades the system’s information flows

- Water accounting / verification (“QuickBooks of Water”) makes conservation auditable, contractible, financeable.

- Work-quality automation (not autonomy theater) delivers finished outcomes + uptime.

- Genetics (heat + salinity tolerance; robotics-ready traits) protects/extends the viable operating window.

- PV / canal cover / spectrum-shaping treats the sun as dual-use infrastructure (cooling + evaporation control + energy).

- Connectivity + edge unlocks coordinated operations, not just data.

5) The deepest leverage point: shift the goal. If the system goal remains “maximize cheap winter volume,” we’ll keep chasing our tail. If the goal becomes “maximize nourishment + reliability per unit of constrained water under climate stress,” incentives, measurement, and innovation reorganize naturally.

Yuma is a blueprint for how real agriculture operates not a morality tale about using “modern” irrigation. The winners (growers + AgTech) will be the ones who preserve the choreography while building the next layer of buffers, feedback loops, and verifiability that makes resilience bankable.

The historical overallocation problem really puts everything in context. The fact that they used data from the wettest 15 years on record to set permanent water allocations is the kind of planning failure that compounds over decades. What struck me most is the gravity is free insight - its easy to assume drip irrigation is always superior, but you show how teh total cost of ownership and the specific constraints of lettuce farming make flood irrigation optimal. The laser leveling acheivement of 80-90% efficiency is impressive given how primitive furrow irrigation looks.